DeVito!

As Cigar Aficionado magazine approaches 20 years in print, we are taking a look back at some of the most memorable stories we have published over the years. In this step back into our vaults, we go to 1996 when we profiled the talented Danny DeVito.

Monday is gardener's day on Danny DeVito's narrow cul-de-sac high above Sunset Boulevard in Beverly Hills. On this particular Monday, the crowded street is, as usual, alive with the sounds of more power mowers, leaf blowers, pickup trucks and foreign accents than you can shake a rake at. Navigating the street to turn into DeVito's driveway is like trying to maneuver among the cheek-by-jowl stalls of some international open-air market.

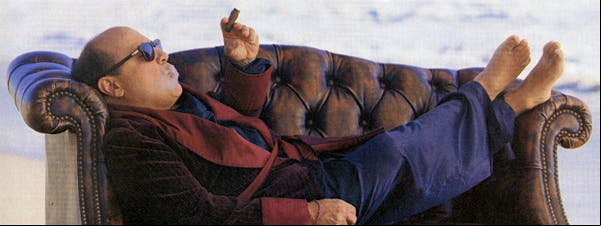

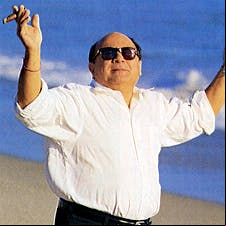

But inside the DeVito compound—behind the large, electronically controlled gate and the security system—all is tranquil. The master of the house—52 years old, 5 feet tall, balding, a little overweight—is strolling about in a long-sleeve blue shirt, dark blue slacks and rubber shower sandals. His shirt is open at the collar. Both shirt cuffs are also unbuttoned (but not rolled up), and for some inexplicable reason, he's wearing the shower sandals over socks. As he shuffles down the driveway, greeting a visitor and various staff with the same blend of warmth and wisecracks for which his on-screen persona is best known, he seems like the world's shortest—and most relaxed—pasha.

"Park here and give your car key to Penny," he says, pointing to one of his assistants. Then, grinning, sotto voce to Penny: "See how much you can get for the car." Penny laughs. We walk inside.

"How about some coffee," he says, then—sotto voce to Pam, another aide—"Try using the good stuff for a change, OK?"

|

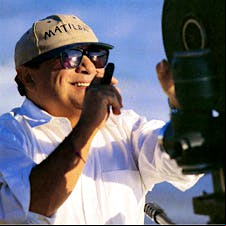

Everyone laughs. Obviously and justifiably pleased with himself, DeVito escorts his guest to the patio—one of two at the house—and almost immediately, tranquility yields to what appears to be pent-up frustration and anger. Unprompted, DeVito begins complaining about studio and media treatment of his most recent movie, Matilda, which he directed and starred in and which he has a special feeling about because it was based on a Roald Dahl book that was first brought to his attention by his then-10-year-old daughter, Lucy.

Matilda, like many DeVito movies (and several Dahl books), is a dark comedy, the story of a little girl who is a budding genius but whose vulgar, dim-witted parents (played by DeVito and his real-life wife, Rhea Perlman) are too self-absorbed to notice or care. Matilda is sent to a school run by a principal whom one critic called "the most disgusting, sadistic, terrifying principal I've ever seen." But with the help of a sympathetic teacher and her own telekinetic powers, Matilda ultimately prevails on both the domestic and scholastic fronts.

Many critics praised DeVito's direction ("bravely subversive dramatization"—The Washington Post) and his acting ("DeVito can certainly be forgiven for stealing his own movie, since he does it in such jaunty high style"—The New York Times), and the trade paper Variety predicted upon its release that Matilda had "definite sleeper potential and could very well outgross many more highly publicized and star-studded summer releases." But other critics found the movie too harsh, cruel and scary for young children, and it wound up something of a domestic box office disappointment in certain quarters, given what it cost to make.

The film took in more than $8 million in gross receipts the weekend it opened, but audiences shriveled fairly quickly thereafter, and in the eighth week of its release, it took in only $108,000. Still, it grossed more than $30 million by summer's end, and as DeVito points out, it wound up "the number one non-Disney family film of the summer."

"With the foreign box office receipts and video, it'll go through the roof," DeVito says. "It's not Independence Day, but is that what the studios and the media are telling us—'You either do ID4 numbers or you're a flop'? That's sick." He pauses. "Besides, if the studio had really gotten behind Matilda...." His voice trails off.

Didn't he urge the studio to it vigorously? Didn't he complain when it didn't?

"Sure. But if the studio is not behind your movie totally, you can call and fax and complain about ads and do anything else you want, and it's like pissing in the wind."

Complaining about "the studio"—in this case, Sony Pictures and its TriStar subsidiary—is as common in Hollywood as complaining about the White House in Washington, D.C., even for someone as successful, respected and well-liked as DeVito, who has acted in, directed and/or produced more than 50 films.

"Hollywood is a jungle," DeVito says. "It's full of quicksand, vermin and flesh-eating beasts. Making a movie is not a walk in the park. Every movie is like navigating treacherous terrain.... There are a lot of good people in Hollywood, but every once in a while, someone gets a top studio job who doesn't know anything about filmmaking...doesn't know what the fuck it is to make a movie."

DeVito is especially incensed, he says, that the studio leaked word to the media that Matilda cost almost $50 million to make, rather than the $35 million acknowledged by DeVito's production company, Jersey Films. DeVito insists the $35 million figure is correct, and he worries that given the box office returns so far, the $50 million figure "sends a message [to the investment community] that non-Disney kid movies don't make money.

"Why would a studio want to do that?" he asks. "Is that the way you want to go to sleep at night—thinking, 'Wow, I really fucked that movie up!'?"

|

This is not the first time that DeVito has clashed with Sony, which may for the intensity of his anger today. But on Matilda, he had to suffer an added indignity: "The studio wouldn't let me smoke on the set." DeVito says he lit up a cigar once and was told it was against fire department regulations, so he promised not to do it again. "But they hired a full-time fireman to keep an eye on me anyway—and they made us pay for it."

Fortunately, DeVito has always been enormously popular with his crews, and the crew on Matilda quickly erected a special "smoking tent" for him outside the sound stage, outfitting it with chairs, a table, a telephone, plants and a large ashtray.

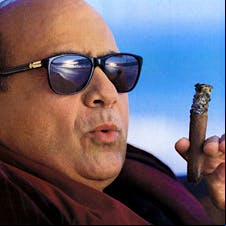

"I like to smoke when I'm working," DeVito says. "Usually, I smoke one cigar a day, after lunch, but when I'm working, I smoke more. It helps relax me."

DeVito says his father smoked DeNobilis, an inexpensive, Italian-style, machine-made cigar that young Danny found "a little rough" for his adolescent taste. In his early days as an Off-Off-Broadway actor in New York, he occasionally bought some DeNobilis himself, but he says cigars were "mostly on the back burner" for him for a long time, and he came to appreciate them only gradually.

In the late 1970s and early '80s, when he was starring in the hit television series "Taxi," in which he played the lovable louse Louie DePalma, he and the other key players in the show got into the habit of coming together for various special occasions—birthdays, weddings, the opening of a new season—to have a nice meal, open a box of Cuban cigars and in a celebratory smoke.

It wasn't until meeting Arnold Schwarzenegger that DeVito began to smoke cigars regularly. While filming Twins in 1987, Schwarzenegger gave him a box of cigars. "I was on a major diet then," DeVito recalls, "so Arnold being Arnold, he also gave me a dozen pastries."

DeVito didn't eat all the pastries. But he did smoke all the cigars, and sometime after that, he began making them part of his routine—first just on weekends and now, every day. His favorites are all Cubans. He began with Cohibas, switched to Partagas Serie D No. 4 after a few years and recently switched again, to Diplomaticos. "Now I'm starting to have a big leaning toward Bolivars," DeVito says. "It depends on my mood and where I am and what I'm doing. When I'm not working on a movie, I like to get up in the morning and take the kids to school, come home and read and work out and have a good lunch and come outside and fire up. A Bolivar seems nice then."

As DeVito speaks, his two dogs—Ocean and Pepper—walk over, looking for a little attention. He pets them both and, in his sternest director's voice, tells them to go away. They ignore him and lie down. But all this cigar talk reminds him of his favorite cigar story:

"I was flying to Europe right after we finished The War of the Roses. It was an all-night flight. We had a great meal and they were going to pour some Port and I had a stogie with me and there were only a handful of people in first class. I had had a couple of drinks and I was with friends and I was feeling good. It was just the perfect time for a nice stogie. The flight attendants had been real friendly, so I said, 'Boy, I would really love to fire up now.' They said, 'You really can't.' I asked why not. They said the engers would be really upset. I said, 'What if I asked every enger on the plane—first class, coach, everyone—if they minded?' One of the flight attendants said, 'Well, OK, if you get everyone's permission.'

"I got up and walked the full length of the plane and said hello to everyone who was awake and asked if I could smoke. Everyone said OK. But there was one guy in the back of the first-class cabin who said, 'There is no way you are going to light up a cigar on this airplane' "—DeVito smiles his slyly malevolent movie smile—"'unless you give me one.'"

|

DeVito fairly cackles with joy at the recollection.

"It was the most enjoyable transatlantic flight I ever had."

Danny DeVito was born in 1944 in the shore town of Neptune, New Jersey—hence the name of his production company—and raised in neighboring Asbury Park, the youngest of five children (two of whom died before he was born). His father owned a pool hall, and Danny became adept with a cue at a young age; even now, he has a pool table in his home. He was a streetwise teenager whose love of movies and sense of the theatrical developed early. Once, while eating ice cream with some friends—one of whom happened to have a starter's pistol—he decided on a bit of impromptu street theater: he staged a fight that involved a phony shootout between two of his friends, after which he and his cohorts jumped into a car owned by the father of one of the friends and raced off into the dark night, while bystanders gaped in stunned silence. DeVito later restaged the event and filmed it as A Lovely Way to Spend an Evening.

But he didn't go straight from the streets of Jersey to the sound stages of Hollywood. There were several detours along the way.

"I wasn't sure what I wanted to do when I got out of high school," he says. College didn't seem a likely or desirable option, "and I didn't want to go too far away [from home]. I was sort of hanging out at the house, and one day, my sister Angela said, 'Why don't you become a hairdresser and work for me at my salon?' I figured, well, I'm not doing anything else, and I could meet a lot of girls there."

Girls had not played an especially large role in DeVito's adolescent life, in part because of his height. "When I was young, I always wished I were taller," he says. "I was plagued; I couldn't slow-dance with the girls I wanted to because my face would be in a spot where I might be thought of as"—shy grin—"moving too fast."

DeVito says his diminutive stature made him a bit bashful as a youngster. It also made him a target for neighborhood toughs. "I took a lot of lumps," he says, "but I had a lot of friends who helped me and looked out for me."

DeVito didn't have any major romances in his sister's beauty salon, and after 18 months, he realized he could probably make more money as a cosmetician than as a hairdresser. He saw an ad and tried to enroll in a makeup class at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York. To get into the school, DeVito had to do a monologue. A longtime film buff— "ever since I saw Battle of Algiers" (the 1965 masterpiece by Gillo Pontecorvo)—he figured that he might as well take some acting classes, too.

It didn't take long for him to see that acting was his true calling. After two years at the American Academy, he got a job in summer theater and went to the Eugene O'Neill Foundation in Waterford, Connecticut, where he met Michael Douglas, later to become a major figure in his life, both personally and professionally. About that time, DeVito read the serialization of Truman Capote's In Cold Blood in The New Yorker, and when he heard that the book was being turned into a movie, he decided he just had to play one of the killers, Perry Smith. He headed for Hollywood. Robert Blake had already been cast for the part, but DeVito stuck around for a while anyway.

"I worked as a car parker and I hung around the Sunset Strip with all the flower children," he says. "I had long hair and I wore a raincoat and sneakers and I fit right in. But I wanted to act."

People told DeVito, "Nobody wants a five-foot character actor," so he returned to New York, began making a few films with his own 8mm camera and worked in a few Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway productions. At a performance of one of them, The Shrinking Bride, an aspiring actress from Brooklyn named Rhea Perlman was in the audience to see a friend, who was also in the cast. The three of them went out afterward. Two weeks later, DeVito and Perlman were living together in a Manhattan apartment that they sublet from Douglas.

|

In 1970, DeVito landed a role in a stage revival of Ken Kesey's classic One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, and soon thereafter, he was making frequent appearances in small films and producing his own even smaller films. Then, in 1975, came DeVito's first big break: Douglas produced the movie version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and asked DeVito to reprise his Off-Broadway role. Cuckoo became the first movie in 40 years to sweep the top five Academy Awards—best picture, actor, actress, director and screenplay—and even though DeVito himself didn't win an Oscar, the movie gave him both the visibility he had previously lacked and yet another powerful friend: Cuckoo star Jack Nicholson.

Ironically, Nicholson had grown up just a few towns away from DeVito in New Jersey. (The two had never met, although DeVito says that when Nicholson first went to Hollywood, he heard quite a bit about the local boy who was trying to become a movie star.) After working together on Cuckoo, "Jack started telling every director he worked with that he should hire me," DeVito recalls, the gratitude still evident in his tone of voice. Not too many directors followed Nicholson's advice, but DeVito found enough roles on his own to shed whatever residual insecurities he had about his height.

"Once I started acting, I realized that my size made me unique," he says. "That opened me up, made me deal with it in a positive way and see the positive side of it. Hell, if I was one of six guys auditioning for a role, I knew I'd be the one who was most different from the others—and maybe that would be just what the director was looking for."

DeVito teamed with Nicholson again in Goin' South and that same year—1978—he began his five-year run as Louie DePalma, the adorably tyrannical dispatcher in "Taxi" (a role that won him a best ing actor Emmy in 1981). He originally got the role after flinging the script on a table during his audition and saying, "One thing I want to know before we start: Who wrote this shit?" That flip, smart-ass attitude became an integral part of Louie's character—and of many, if not most of the characters that DeVito has played since.

When ABC canceled "Taxi" after a four-year run, DeVito was devastated. He thought the show had the creative energy and audience popularity to last another five years. He later told Playboy, "I don't think that the people at ABC gave a good rat's ass about 'Taxi.' " NBC picked "Taxi" up for a year, which gave the cast and crew a brief, bittersweet reprieve, but by then, DeVito was A Star.

He teamed again with Jack Nicholson in of Endearment and with Douglas in Romancing the Stone and The Jewel of the Nile, and he went on to perfect his demonically comic, funny-but-sinister persona in a series of high-visibility movies—Ruthless People, Wise Guys (DeVito's first top billing), Throw Momma From the Train (his directorial debut), Tin Men and The War of the Roses.

Douglas calls DeVito the "Prince of Darkness;" but perhaps because DeVito is so small, perhaps because his head is a bit large for his body, perhaps because there is almost always at least an undercurrent of humor in his behavior, DeVito seems vaguely cartoonish on the screen, even when he's being nasty and brutish. As a result, the audience never sees him as entirely villainous. He always arouses a certain empathy, if not sympathy, from audiences.

"I love slapstick," he says. "I'm a big fan of Jerry Lewis and the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. But my heart belongs to dark comedy. I feel a kindred spirit to that kind of humor. I like movies that point out the absurdities in life."

DeVito especially enjoys directing—"film is a collaborative effort, but the director has the final say"—and having acted in Twins and Junior with Schwarzenegger, he says he'd really like to direct him in a movie. "He's a very good actor, very spirited and dedicated to his work. I loved working with him. But he has to take the next step now. He keeps doing the same movies over and over again. He has to take some chances."

Has he told Schwarzenegger this?

"No." Big smile. "I'm telling you."

|

DeVito has taken some chances himself, most notably with Hoffa, the 1992 dramatized biography of the former Teamsters union boss that marked DeVito's first major producing credit. Hoffa was DeVito's most ambitious—and most controversial—project. He acted in it and directed it, and his work generally drew high praise. "DeVito emerges here as a director of impressive visual scope and flair," said Kenneth Turan in the Los Angeles Times. Vincent Canby, writing in The New York Times, called Hoffa "a remarkable movie, an original and vivid cinematic work...conceived with imagination and a consistent point of view."

But many critics objected to what they saw as DeVito's (and screenwriter David Mamet's) overly sanitized view of Hoffa, the labor leader turned convicted felon who disappeared and was presumed murdered in 1975. When Hoffa was released, DeVito was quoted as defending his version of Hoffa—portrayed brilliantly by Jack Nicholson—as a man with the "biggest balls in the world," someone who, "in my opinion, from what I've learned about him...would have made a great president...of the United States." Nevertheless many denounced the film's glossing over of Hoffa's ties to the Mafia, the plundering of the Teamsters Union treasury during his tenure and the pervasive efforts to corrupt public officials. They also questioned the one-sided portrayal of Attorney General Robert Kennedy as a power-hungry egomaniac versus Hoffa, the crusading, working man's hero. DeVito says, "Our research led us to believe we were right." But the controversy still makes him a little uncomfortable. "I am sorry about one thing with Hoffa," he says. "I understand the Kennedys were hurt by it and I regret that....Would I make Hoffa 2? Probably not."

But Hoffa did not sour DeVito on producing—far from it—and Jersey Films has since been responsible for a string of unusual and highly respected movies, among them Reality Bites, Pulp Fiction, Get Shorty and Matilda. Unhappy at Sony/TriStar, where for four years Jersey had what is known in Hollywood as "an overall deal" (in which the studio finances and distributes the movie), DeVito has recently moved his production company to Universal Studios. Sony "didn't want to make...our movies," he says. "What's the matter, man?" He feigns sniffing both his armpits. "I felt absolutely alone at Sony."

DeVito becomes very ionate about, and totally committed to, the movies he takes on. It's part of his charm, his success and his popularity with his collaborators. At one point in the negotiations with TriStar over Pulp Fiction, he stood on an executive's desk and insisted the executive not leave the room until a particular point of the deal was settled. The executive finally agreed to give DeVito what he wanted on that point, but TriStar wound up ing on Pulp Fiction, which was made for Miramax Films, much as Reality Bites was made for Universal and Get Shorty was made for MGM.

Several other prominent producers have also left Sony recently, so DeVito is hardly alone in his disenchantment with the company, which has been undergoing major upheavals for the past couple of years. Now happily ensconced at Universal, he and his Jersey colleagues Michael Shamberg and Stacey Sher are looking forward to the release next spring of Gattaca, a futuristic movie about the dangers of genetic engineering. They are also awaiting a script on Out of Sight, based on the latest novel by Elmore Leonard, who also wrote Get Shorty.

In Get Shorty, a loan shark from Miami who wants to make movies says, "I don't think the producer has to do much, outside of maybe knowing a writer," and while DeVito got a big chuckle out of that line, he says today what everyone who actually does make movies knows: "Producing is hard work. You have to deal with ants and lawyers who have no idea what really goes into making a movie. It's a constant fight. Like when I was growing up in Jersey, you have to keep running away from the bad guys." He shakes his head. "But fighting a battle and winning is fun. And this business is fun. I love it. It's the greatest business in the world."

Part of what makes the movies fun for DeVito is the variety—acting, directing, producing, promoting. Two days after our interview, he ed the cast of Michael Douglas' newest production, Rainmaker, to be directed by Francis Ford Coppola, based on John Grisham's best-selling novel. He's also constantly on the lookout for fresh directing and producing projects.

DeVito enjoys new challenges and—already a computer buff, with a special, newly installed line at his house for connecting at high speed to the World Wide Web—his newest interest is mastering the Internet, for which Jersey Films is now developing its own Web page.

|

"You can't beat it as a movie marketing tool, as an information tool," he says. "I'd love to be able to go on-line when we're making a movie and tell people what's going on behind the scenes. What a way to build an audience."

DeVito has six computers at home—three belong to his children, Lucy, now 13; Gracie, 11; and Jake, 9—and he says he spends about an hour a day "surfing the Net." A devoted father, he increasingly tries to avoid going out of town unless he can take the family with him; when he is on location, he takes his laptop and digital camera and sends photographs to his children by computer: "Here's me. Here's my hotel room in Australia. This is the view from my balcony at night."

He's very serious about, and very protective of, his children. Always has been. "My dad told me that my baby sister died at one month after she was exposed to someone who came to the house with whooping cough," he recalls. "When I had my first baby, I wouldn't let anyone but Rhea near her for two weeks. Our relatives were up in arms. But I stuck to it and Rhea backed me up."

Are his children equally protective of him? How do they feel about his cigars, for example? "They question me about them. It's a real tough subject to talk about with your kids. They don't want you to be hurt. They want to protect you. So I explain about how you don't inhale cigars." He also tells them that cigars aren't addictive and that he doesn't smoke that many of them.

At home, DeVito says, he avoids smoking in or near the children's bedrooms and tries to smoke only on the patios or his screening room or smoking room, "although I sometimes fire up at the dinner table after a dinner party when I just can't move."

He laughs and stands for only the second time in the two hours he's been talking. We walk across the patio, into his screening room and down a narrow, winding stairway to the smoking room. It's ed with dark wood and filled with overstuffed furniture and more than a dozen ashtrays. He opens a medium-sized humidor—"I have three of them, plus a couple of traveling humidors"—and lights up an Hoyo de Monterrey robusto.

"What I really like," he says, "is to sit with a bunch of guys and have a nice meal and smoke a few cigars." But his rhapsodizing is interrupted by a phone call; it's his wife and occasional co-star. Perlman, who won four Emmys for her portrayal of Carla, the wisecracking waitress in "Cheers," is calling from the set of "Pearl," the new CBS sitcom that she co-produces and stars in as a middle-aged college student opposite Malcolm McDowell, who plays the snooty Professor Pynchon. (Educating Rita comes to prime time.) DeVito and Perlman swap reports on their day's activities—"I'm a man of leisure this week," DeVito says—and he laughs repeatedly at her of life in episodic television. Then, a man of leisure indeed, he strolls back to the sofa, takes a deep drag on his cigar, smiles beatifically and says, "This is the life, huh?"

David Shaw, the Pulitzer Prize-winning media critic for the Los Angeles Times, is the author of The Pleasure Police: How Bluenose Busybodies and Lily-Livered Alarmists Are Taking All the Fun Out of Life (Doubleday, 1996).