Cuba’s Classic Car Détente

Ray Magliozzi is sitting on a stoop of the Hotel Capri in Havana—the last hotel built by mafia don Meyer Lansky before the Cuban revolution—with about six minutes left on a Romeo y Julieta he is smoking. A replica Ford Model T taxi pulls up to drop off engers. Magliozzi, who is arguably the most renowned auto mechanic in the United States, engages the young female driver, Yemey, in an animated discussion of the creative repairs she has made, and all the parts she needs but can't get, to keep the car on the road. She pops the hood to show him how she replaced a broken generator on the transplanted VW engine that powers her car. "Her original generator had given out," Magliozzi explains. "So without a ready replacement the mechanic welded a bracket to the failed unit and retrofitted the charging system with a General Motors alternator which got bolted to that bracket. Pretty clever!"

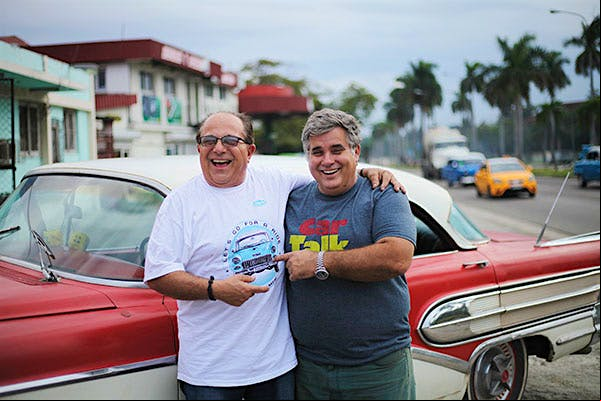

The now retired cohost of "Car Talk," the wildly popular program on National Public Radio, has come to Havana to meet the mechanics, owners and drivers who are responsible for the automotive oasis of classic American cars that populate the streets of Cuba. "We are trying to ascertain how these cars stay on the road," as Magliozzi describes his mission. The 1930s-, '40s- and '50s-era Studebakers, Hudsons, Chrysler Crown Imperials, Buick Century Rivieras, Chevy Bel Airs and Styleline Deluxes, Ford Edsels and Fairlanes, among so many other long-extinct Detroit models, are alive and well in Cuba. These so-called "yank tanks" have long been a ubiquitous part of Cuba's national landscape and cultural identity—and are now emerging as a critical component of the nation's steady evolution away from strict socialism toward a mixed market economy.

For car aficionados such as Ray Magliozzi and the small team of "Car Talk" producers and writers who have accompanied him to Cuba, watching these classic automobiles traverse Havana is a trip down memory lane. In Cuba he has had the chance to hop behind the wheel of a 1929 Ford Model A, tootle around town in a '59 Buick Special, and tune the engine of a 1958 Chevrolet Impala. During visits to restoration garages and auto shops Magliozzi compared notes with fellow Cuban mechanics on make-shift clutches, jerry-rigged exhaust manifolds, front-end alignments, master cylinders and bell cranks—all repaired without access to original parts or modern machinery. "I've been constantly impressed by the cleverness and the sheer determination of the people who keep these cars going," he marvels. "It's amazing."

The president of the United States shares his opinion. During Barack Obama's history-making trip to Havana last March, he also highlighted the resourceful, entrepreneurial spirit of the Cuban car community. "Here in Havana, we see that same talent in cuentapropistas [small business entrepreneurs]...and old cars that still run," he said during his speech to the Cuban nation. "El Cubano inventa del aire," the president declared, switching to Spanish for emphasis. Cubans invent things out of thin air.

Cuban Cacharros

When it comes to their cacharros, as the older autos are affectionately referred to, inventive Cubans have made a virtue out of necessity. Newer cars are simply not available to the vast majority of Cuban drivers—even though Raúl Castro announced in 2013 that as part of his economic modernization plan Cubans would finally be free to purchase new cars. When the few state-owned dealerships opened in January 2014, potential customers suffered severe sticker shock: $262,000 for a Peugeot 508—a car with a MSRP of about $30,000 in the United States. Cuban government markups on such used cars as a 2010 VW Jetta, which went for more than $50,000, were also prohibitively exorbitant. "The Communist Party doesn't want Cubans to be able to drive around in new cars because they are status symbols," one chauffeur explained to Magliozzi and his team during a city tour—in a 1950 Ford—on their first night in Havana.

With no realistic ability to purchase a new car and limited access to affordable used cars that actually run, Cubans have no alternatives to keeping the old cars on the road for as long as possible—60, 70, even 100 years. "Cubans and their cars are like a marriage," observes my Cuban friend, Edel. "Till death do us part."

An estimated 60,000 American-made cars are on the island—almost all of them dating back to the early and mid-20th century heyday of the big three Detroit automakers. "The narrow old streets are jammed with big American automobiles," The Nation magazine reported in January 1928 when President Calvin Coolidge became the first, and, until Obama, the last U.S. president to visit the island. By the 1940s and '50s when Cuba had become a playground for the American rich and famous, as well as the U.S. mafia, the country also became a national showroom for shiny, new, Detroit-manufactured automobiles. Ford, Chrysler, Chevrolet and Cadillac dealerships lined Havana's leafy Prado boulevard. Indeed, Cuba gained the dubious distinction of importing more Caddys—Fleetwood convertibles, DeVilles, Eldorado Broughams—than any other nation in the world.

The 1959 Cuban revolution put a dramatic end to the ostentatious, chrome-plated display of wealth on the island. In constructing a new Cuba society, Fidel Castro made it clear that his revolutionary regime would focus on agricultural development and socialist egalitarianism. "We need tractors, not Cadillacs," Fidel famously declared. The car dealerships were expropriated, along with other private enterprises. Many of the Cuban bourgeoisie fled to the United States, leaving businesses, mansions and their cars behind.

President John F. Kennedy's imposition of a full trade embargo in early 1962 deprived Cuba of its natural trading partner. The bloqueo, as Cubans call it, created a crisis for the economy, and opened the door to a long era of Soviet economic assistance—as well as the importing of Eastern Bloc cars such as Ladas, Polskis, Volgas and Moscovitches. No American-made cars have come to Cuba since. Nor, until very recently, were any replacement auto parts available.

Initially, as Magliozzi points out, the Cubans had spare parts on the island. After those were used up, he says, Cuban mechanics cannibalized other American cars that were there "and when they ran out of what could be scavenged, they ran into ingenuity." For years, Cubans have molded and manufactured car parts by hand, using sheet metals, re-melted iron and plastic, even wood. What they couldn't make, they would modify. Car owners with resources might restore the body of a vintage Buick Roaster, Olds Deluxe 88, Chevy Bel Air or Cadillac Fleetwood to outward perfection, but underneath the hood would be a transplanted diesel engine from a small Eastern European truck or one of the Japanese or Korean cars Cuba has imported over the years. (One particularly enterprising mechanic, Jote Madera, managed to salvage the motor of a confiscated drug runner's cigar boat and retrofit it into his 1951 Chevrolet Business Coup, known to Cuba's drag racing community as "the Black Widow.")

Beyond the engine, almost every old American car moves on parts from a variety of other newer foreign vehicles. Innovative mechanics have managed to create what Cuban journalist José Raúl Concepción calls "Fordyotas" and other kinds of "functional automotive Frankensteins" that are now a major component of Cuba's socioeconomic environment and cultural heritage.

Automotive Ambassadors

Many of the unrestored old cars that rumble up and down Havana's streets are indeed metal monsters—unsafe, falling apart and spewing exhaust. The almendrones, as Cubans call the taxis which circle in a fixed loop through the city, are uncomfortable, potentially dangerous and, according to a recent investigative report on the website Cubadebate, increasingly expensive for the majority of citizens who still garner a state wage of about $22 a month. Many Cubans outside the tourist sector see the cars as a symbol of the decrepit state-run system of inadequate and antiquated public transportation. There is no nostalgia for the old cars. Rather their omnipresence on the roads is a clear reflection of Cuba's abject failure to modernize. If given the chance, observes Magliozzi, Cubans "would lunge at the chance to own a new car."

For tourists, however, the result of Cuba's automotive ingenuity is a unique parade of mobile Americana—a moving exhibition of Detroit-styled steel on wheels. "Cuba is by far the largest American car museum in the world," writes photojournalist and tour guide Christopher Baker in his glossy photography book, Cuba Classics. "There is no more singularly Cuban image than a voluptuous yank-tank of yesteryear basking in the tropical sunlight."

Indeed, along with cigars, rum, salsa music, and a curiosity about the Cuban revolution itself, the vintage cars have become a leading tourist attraction. Since December 2014, when Presidents Obama and Castro announced a breakthrough in relations, the number of U.S. travelers has increased by an estimated 80 percent. Direct flights on such airlines as United, JetBlue and American Airlines are due to begin later this year, when some 450,000 Americans are expected to the 3 million visitors to Cuba from other nations. Many of them will take a joy ride in one or more of the classic autos. "The trip doesn't feel complete unless you climb into one of these cars," Baker noted in an interview with Cigar Aficionado. "It would be like going to Paris without climbing the Eiffel Tower."

While Cuba's tourism boom is creating shortages of everything from hotel rooms to beer, the influx of visitors is generating revenues and incentives for the cars' owners and drivers. More and more meticulously restored cars are appearing on the roads—especially convertibles, which command fares as cars-for-hire and taxis. And more and more drivers are obtaining government approval to become self-employed chauffeurs, expanding Cuba's small but growing private sector. The story of the cars, suggests Collin Laverty, who runs Cuban Educational Travel and has recently purchased a beautifully restored, two-tone, 1938 Ford Sedan Delivery for business use on the island, "is the story of reform, a newfound private sector, and the re-emergence of economic, political and cultural relations between the U.S. and Cuba."

Indeed, each car, and each driver, has a special story relating to Cuba's complicated history and its current socioeconomic transformation—stories that are often shared with engers. Beyond offering transportation opportunities, both the cars and the drivers have become essential cultural ambassadors as they provide a positive point of —and common ground—between foreigners and Cubans. "It isn't just a pursuit of a career and money," as Magliozzi observes about the people in the car community he has met in Cuba. "They really love their cars." That love is shared by many of the tourists who hop in for a ride.

One of the first owner/drivers Magliozzi meets on his trip is Ramón Gonzalez, a 70-year-old Cuban from the province of Santa Clara. Gonzalez is the proud owner of a red 1929 Ford Model A—it still has its original motor—which he bought in the mid-1990s for about $600 and restored himself, part-by-part, over the course of a decade. A former professor of mechanics, Gonzalez drove the car across the country to Havana several years ago to take advantage of Raúl Castro's economic reforms, which opened the door to private sector taxi drivers. He now ferries tourists up and down the Malecón, the seaside boulevard that separates the city from the ocean.

For the "Car Talk" team, he has assembled the unofficial "Ford Model T Club." The group of cars includes another pristine 1929 Model A, owned by Nelys, a former doctor who abandoned a career in medicine in the state sector for the considerably higher income of a taxi driver in the new private sector. Her bright green Model A is ed by several other vintage models, including a 1914 Ford Model T, owned by Reiby, an older Cuban man who acquired the car during an inheritance conflict after the original owner ed away. A five-car caravan of very old Fords carries the "Car Talk" entourage to the outskirts of Havana where they can drive the cars themselves. When Gonzalez's Model A hits a pothole and the engine cuts out, he jumps out, lifts the hood, and fiddles with the wiring. "The ignition coil wire popped off," predicts Magliozzi, who became famous on "Car Talk," along with his older brother Tom, for being able to identify and solve automotive problems on the radio without actually seeing them. "On this car it is easy to just pop it back on."

Nostalgic Cars

For 25 years between 1987 and 2012, "Car Talk" was NPR's most popular show. More than 4 million listeners tuned in every Saturday morning to hear Ray and Tom—they called themselves "Click and Clack, the Tappet brothers" on the show—field call-in questions about people and their cars. Through quick wit and sage advice, they would diagnose and solve the callers' problems and concerns—even ones that had nothing to do with automobiles. The show was distinguished by the banter between the two Magliozzi brothers and by their peals of laughter—particularly Tom's infectious guffaws. "It's hard to any person whose laugh changed an entire industry," observed Charlie Kravetz, the general manager of WBUR, the NPR in Boston where "Car Talk" got its start. "Everybody in public radio would tell you there's a line in the sand: There was everything before ‘Car Talk' and after ‘Car Talk.' We all owe them an enormous debt." The "Car Talk" duo "are culturally right up there with Mark Twain and the Marx Brothers," said the program's longtime executive producer, Doug Berman, in a eulogy to Tom, who died of Alzheimer's disease in November 2014. "They will stand the test of time."

Led by Berman, the "Car Talk" team maintains a dynamic and popular website—cartalk.com—and counts some 600,000 followers on its Facebook page. In a tribute to Tom, the radio show has been renamed "The Best of Car Talk" and continues to be broadcast weekly on hundreds of NPR stations. Even in reruns it remains one of the highest-rated radio shows in the United States. "I sometimes listen to the show just to hear my brother's voice," Ray told me during the trip to Cuba. At age 67, he has recently stepped back from running the "Good News Garage" that he owned with his brother, handing off management to one of his lead auto mechanics.

In Cuba, Magliozzi finds an auto garage also owned by two brothers, Paul and Felix Gómez. The repair shop known as the "Casino" was opened by their father, Eliecer Gómez, and operated informally under the radar of the Cuban government for many years. With the recent legalization of independent, non-state-owned garages, it is doing a brisk business in front-end alignments and in repairing the Russian-built Ladas that many Cubans still drive. Paul Gómez shows the "Car Talk" team a Lada engine he is installing, and he and Ray engage in an animated discussion about the 5,000 clutch replacements Paul has done over the years—he keeps a handwritten logbook of every single repair—and his innovative efforts to construct a non-hydraulic clutch apparatus. The two climb down into the pit to examine the front-end alignment repairs on a beat-up Russian Volga.

But it is at one of Havana's preeminent restoration garages that Ray really gets grease on his hands. During a visit to NostalgiCar, Magliozzi gets to work on a 1958 Chevy Impala in need of a tune-up, adjusting the valves so that the "tappets don't click and clack," as he explains. "We are going to do it again," Magliozzi tells Cuban master mechanic, Julio

Álvarez, after one round of adjustments, as he attempts to further reduce the piston noise levels.

NostalgiCar is a prime example of successful small-business entrepreneurship in Cuba's small but rapidly growing private sector. Álvarez and his wife, Nidialys Acosta, started the company in 2012, after a powder-blue 1956 Chevy Bel Air that Álvarez had meticulously restored won a casting contest for use in a Canadian film. Álvarez restores the vintage cars, mostly mid-1950s Bel Airs, and Acosta deploys them as a car-for-hire service in the tourist sector. They now employ eight young mechanics, and generate revenue for at least two dozen drivers. In less than five years, their fleet has gone from two to 22 cars, several of which have become quite famous.

Ray gets to tour around Havana in Acosta's pink and white 1956 Bel Air, nicknamed "Lola"—the same car that Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe drove in last fall when he visited Cuba, and that New York Governor Andrew Cuomo rode in when he came last year. When Secretary of State John Kerry came to Havana on August 14, 2015, to reopen the U.S. Embassy, the State Department asked Álvarez to finish restoring a black 1959 Impala sedan so Kerry could take it for a spin. During the Embassy flag-raising ceremony, the NostalgiCar Impala was positioned on the street behind the flagpole for the world to see.

During his afternoon at NostalgiCar, Magliozzi inspects the rare 1959 Chevrolet Impala convertible that Álvarez has recently purchased to restore. There are only three of them on the island, he tells the "Car Talk" team, explaining the high price he paid. He has already acquired most of the parts to restore the car, paying a 20 percent to a middle man in the United States to purchase the parts and arrange for them to be carried to Havana. "Everybody wants to ride in a convertible," he says. "And that's the cost of doing this business while the embargo is still in place."

The Cars And The Embargo

When President Obama visited Cuba last March—the first U.S. president to do so in 88 years—he hosted a special forum for Cuban entrepreneurs. Julio Álvarez and Nidialys Acosta were invited to attend. They were also among more than 500 dignitaries invited to the venerable Gran Teatro the next day where Obama gave a major speech to President Castro and the Cuban people. "As president of the United States, I've called on our Congress to lift the embargo," Obama said, to a round of applause. "It is an outdated burden on the Cuban people."

Certainly Julio and Nidialys are looking forward to the day when the embargo is lifted, and they can order parts directly from the United States without using a middleman—or even better, buy them from a U.S. auto parts wholesaler in Havana. "For my business, if Obama ends the embargo that would be the best," says Nidialys. "It means more American tourists to rent our cars, more facility to bring in the parts, and to maintain and restore more cars."

Magliozzi agrees. "The embargo doesn't make any sense," he states. "There is no good reason to punish the Cuban people" and lifting it would "help Cuba lift its standard of living." Magliozzi looks forward to the day when U.S. auto parts companies will be able to set up a small factory in Havana, employ Cuban workers and make parts that all the mechanics he has met on his trip can use to advance their repair and restoration businesses, and continue to keep the old classic cars on the road.

With the Republican leadership in Congress dedicated to blocking President Obama's agenda, especially during an election year, it is unlikely the full embargo will be lifted anytime soon. But Obama has been able to use his executive powers to open the door to greater commercial and cultural interaction with Cuba, bringing a lot of attention to the vintage American automobiles. A recent segment of Anthony Bourdain's CNN show, "Parts Unknown," featured the old cars in Cuba. This past spring, the Havana Motor Club, a documentary film about current efforts to legalize the sport of drag racing in Cuba, premiered in New York City. And in April the popular movie franchise Fast and Furious became the first major Hollywood production to film in Cuba, casting more than 80 of Cuba's coolest and fastest restored yank-tanks as extras for its forthcoming sequel, Fast and Furious 8.

In the meantime, U.S. tourists will continue to come to Cuba in droves, many of them hoping for an experience of climbing into the backseat of a vintage Bel Air like Nidialys Acosta's Lola or Ramón Gonzalez's 1929 Model A. "We feel good that the Americans are coming here," Gonzalez told Cigar Aficionado. "We have wanted this for years. We hope that relations continue to improve, that our economy improves and that the little we have we can share." Indeed, when Magliozzi and his "Car Talk" team ran into Gonzalez while exploring Old Havana, he spontaneously invited them into his small apartment for coffee. Magliozzi is now "a friend," Gonzalez says. "I feel happy that this guy drove my car."

Peter Kornbluh writes frequently for Cigar Aficionado on Cuba. He is co-author, with William M. LeoGrande, of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana.