Holy Rollers

If you’ve spent much time in casinos, chances are that you have prayed for a fortuitous card or a roll of the dice or even for the cocktail waitress to bring you a much-needed scotch and soda. It’s the kind of prayer that is nonspecific and doesn’t really come with an expectation of working. As the poker player Gavin Smith once told me, “I’m figuring that God has better things to do.”

Maybe so. But that didn’t stop Christian card counter Dusty Wisniew during a roller-coastering session in a Louisiana casino. “On the first night of the trip I went from $50,000 to less than $4,000,” he recalls.

Card counting, incidentally, is completely legal. It’s a craft that involves tracking cards that have already been dealt in order to calculate a likely advantage on hands. “After every hand I won, I said, ‘Thank you, Jesus.’ I was grateful for each win and for the possibility to be able to sit there and rebuild my bankroll. I went up to $15,000, then down to $9,000 before going to bed.” And the next day? “I got backed off”—meaning that he was asked to stop playing blackjack. Casinos are entitled to halt a player for any reason, even if that player has a legal, mathematical strategy for beating the game.

Wisniew was a member of one of the more unusual card-counting teams in the history of blackjack. Nicknamed the Church Team, this group was managed by Evangelical Christians, who traditionally view gambling as a sin. Many of the players, mostly in their 20s, were recruited through various religious organizations.

Investors in the team’s bankroll consisted mostly of family and friends—predomintantly true believers. It is estimated that the team realized a post-expense profit of approximately $3.2 million over the course of its eight year history, before disbanding in 2011.

At the table, they were not your typical card counters. Team cofounder Ben Crawford, 24 when it started, recalls, “Sometimes, between hands, I would try to talk people out of gambling. I’d ask them what they were doing. I’d tell them that they must know they can’t win. If there’s anything we tried to do, we tried to bring reality to casinos.”

And to take as much money as possible out of the casinos. “We would go to Vegas and play until sunrise,” says Mark Treas, another Christian team member who had a reputation for working longer and harder than his peers. “I used to play standing up so I could bet at one table and count another one. It’s high risk, but from the time I entered the casino I wanted to make more money than anyone else.”

|

Early on, Ben Crawford seemed like a long shot for card-counting glory. He was raised in a strict Christian household and taught through religion that gambling was bad. Sitting near a humidor full of cigars in the well-appointed home office that he’s carved into the top floor of his house in northern Kentucky, Crawford explains that he fell into playing after reading a book on blackjack. He hoped to find a hobby that he could make a little bit of money on. At the time, he, his wife and his wife’s daughter existed on a budget of $200 per week. Crawford waited tables in a restaurant, and he took $800 of his hard-earned money to a casino near their home in Washington State. “I lost the first $800 and then used another $800 that we had in savings to try it again.”

What did his wife have to say? “My wife didn’t care. She wasn’t attached to money. But I kept on winning and winning.”

Inadvertently, maybe because of his Christian beliefs and a comfort in the fact that God would look out for him, Crawford embraced the kind of gambling that may be reckless but is also necessary for building a bankroll from nearly nothing into something pretty big. “I , early on, playing a hand at the Venetian where I lost two grand,” he says. “It was half of my bankroll. But if I played to my roll, I would have been betting $1 units and it would have taken me seven generations to hit $100,000.” So, the thinking went, you could play within your limits or “throw money to the wind. I was never afraid of losing my money. I knew I could always get a job in a restaurant and make $4,000.”

Though wins came much more frequently than losses, early success did nothing to assuage guilt he felt about being in casinos and playing blackjack. Never mind that he made money at it, had fun and clearly operated at an advantage. “I was raised to believe that Christians didn’t gamble,” says Crawford. “I walked out of casinos, thinking the whole thing was a sin. But the situation forced me to think about what was wrong with it. Why was it a sin? It became more complicated. I couldn’t see what was wrong with being in a casino and doing math in your head. I realized that it’s no better to be selfish with your money in a shopping mall than in a casino.”

Mentally freed, Crawford turned to card counting in earnest, playing as many as six nights per week, believing that he had discovered the holy grail of gambling. He enjoyed the prospect of winning, say, $1,000 in a single session and was psychologically strong enough to handle any inevitable losses. Still, though, as somebody who had formerly waited tables and always associated his income with a predetermined hourly wage, blackjack was a revelation. It infused him with an entrepreneurial zeal and showed him that “income could be divorced from the money that a boss is willing to pay you.”

After teaching a Bible camp friend named Colin Jones how to count cards, Crawford had company. They briefly linked up with two other players and formed a small team, which didn’t last due to internal conflicts. But word circulated among young, male churchgoers, and suddenly, Crawford and Jones were being approached for tips on how to play. “That’s when the lightbulb went on that we could train a bunch of people, have a team and not need to play very much,” says Jones who consulted with several church elders before convincing himself that blackjack was not in conflict with his religious leanings. “Our success came from making the team feel more like a family and less like a business.”

Besides creating dedication, the idea was that forging a high degree of closeness would also foster honesty for those involved in an enterprise where you might be trusted with $100,000 in chips and cash. “We wanted it to be that if someone stole, they weren’t just taking money from investors; they were taking money from their family,” says Jones. “We didn’t trust people because of lie detector tests. We trusted people because of who they were.” No doubt, the bonds of Christianity helped to strengthen that trust.

In putting together their team that would eventually have 30 players, Jones and Crawford figured out a payment system based on a percentage of each player’s expected value (that is, the money that each was expected to earn per hour). Finding church friends willing to play was as easy as splitting eights against a dealer’s six.

One of the more enthusiastic recruits was Mark Treas, a big-boned, athletic-looking guy with a buzz cut of blond hair. Like the others, he needed to figure out whether or not attempting to beat casinos at blackjack counted as a sin. He justified it with the rationale that casinos are public places offering games to the public. So what’s wrong with trying to beat the games? Once he decided to play, he spent 30 days “reverse engineering the system in a public library.” Formerly a real estate flipper who partnered on properties by putting up sweat equity, Treas found himself out of work due to a back injury. So he took the time to understand how card counting worked and knew all the moves cold.

To test for the team, he flew from his home in northern Kentucky to where Crawford then lived in Seattle. After ing and being brought on, Treas told Crawford during their first encounter, “I will either own the team or run it.” Crawford, who was soaking in a hot tub at the time, coolly responded, “Well, I guess we’ll make you a manager.”

Treas quickly proved his worth by winning $20,000 the first time he played a Seattle casino—and getting backed off for his trouble. That marked the beginning of a pattern. “Mark hit and ran,” says Crawford. “He played more aggressively than any player I had ever seen. His goal was to get kicked out of every casino he could. And he did. He played a lot of hours and made pretty good money.”

With Crawford and Jones managing the team—dealing with investors, deciding where players would play, tracking results and shipments of money around the United States and into Canada—things ran relatively smoothly. Players were encouraged to invest, but outside investors (including one who believed enough to put in $200,000) covered much of the bankroll

required to a gang of card counters laying down as much as $6,000 on two hands.

If not for the team’s logo—a silhouette of the Las Vegas skyline with a church jutting up out of the center—it almost would have been easy to forget that they were Christians first and card counters second. While the more progressive church deacons seemed to get a kick out of the Christ-loving lads who had a knack for bringing down the houses of Vegas, others were less impressed.

“I was a leader at church and they hinted that if I wanted to move up, I had to stop playing blackjack because it didn’t look good,” Crawford re. “But why would I quit this to do that? This was all I ever wanted to do: reach young guys and counsel them on getting out of debt, on marriage and on children. I bought out people’s credit card debt and let them pay me back at reasonable interest. I coached guys and helped them figure out what they were good at. I showed them how to think out of the box. I felt like I was doing more ministry on the team than I was doing in the church.”

Besides, Crawford adds, “The whole [Christian] thing was ironic. People sometimes mistook us for a church. But we weren’t a church. We were a blackjack team that had Christians on it. It was something we all had in common and it was fun. We sent out a team newsletter called The Sunday Morning Church Bulletin.”

Entertaining as Crawford may have found it to be, once the gambling tables were hit hard by the team , casino bosses were less than amused. And, unlike in the early days, Crawford did sweat the money, largely because it wasn’t all his. He felt a responsibility to investors. Plus there were unanticipated incidents that needed to be dealt with, like, for instance, the time that a player misplaced $10,000. He eventually found the cash—inside his sofa—and returned it, but Crawford considered throwing him off the team for being so careless. In another instance a player’s ouster from the team was influenced by a teammate claiming God had told him that this player was stealing money. Then there was the time that a player had $100,000 seized from him at the Canadian border due to a declaration snafu. All the praying in the world couldn’t straighten out that mess. Crawford figures he spent 40 hours getting the money back and that the mistake cost the team $10,000.

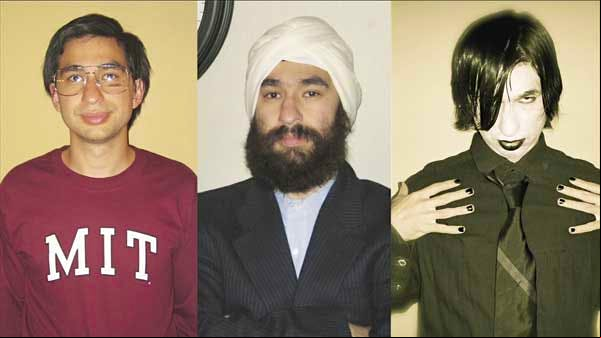

As the players became increasingly known to casino security, they resorted to outré costumes. Crawford himself dressed up as an Indian businessman (complete with a turban and a suit), a “gangsta” and a goth. Mark Treas took it a step further. “In Mississippi, I started out super urban and got backed off everywhere,” he says. “Then I shaved off my beard, changed into a jacket and tie, and returned as a different person on the same night. That bought me some more time. In Atlantic City, I played the persona of an aggressive Russian guy. I’d point at the pit boss and tell him to get me water.”

Besides an hourly rate received for playing, the comps and gifts were fabulous. Treas sold wristwatches and gift cards on eBay. He once had a $2,000 shopping credit at the Hard Rock and called in a friend to spend the money for him—“I get my clothes from thrift shops, so it made no sense to me,” says Treas—and he changed his name three times to keep the comps coming in.

Away from the tables, though, he didn’t exactly live a Vegas lifestyle. One highlight for him is the night that he spent with a group of fellow Christians. After getting backed off at M Resort, he went to a friend’s home for a night of spiritual songs and dinner. Casino hosts would ask what they could do for him and Treas, a vegetarian, would be happy with a salad. “In my world, I would play all night and go back to the hotel room,” he says. “I don’t watch television, so I would throw away the batteries in the remote. What Vegas sells is not what I am consuming. I am faithful to my wife, and Las Vegas is no place for a man who wants to be faithful to his wife.”

But Treas and the others made do. To say they were on a mission from God would be an exaggeration, but it’s easy to see how their Christian morals kept them focused on the job at hand as they took millions out of casinos across the United States. It ran to plan for six years, with investors making as much as 200 percent in a single year and players earning up to $200 per hour for their time at the tables. But the back-offs became increasingly aggressive. Players were no longer being asked to not play blackjack in the casino; they were actually getting 86ed. Sometimes local law authorities were called in. Other times, particularly on the Indian owned casinos, players were taken into backrooms and threatened.

Opportunities for good games began to thin.

The desired plan when heat came down was to gather your chips and get out of the casino as quickly as possible—praying or not praying—as you hustled for the exit. Treas met his match one night at Wynn Las Vegas. “Guys were chasing me, I got out of the Wynn and was running along the parking lot’s slippery cobble stones, sliding around on flip-flops, and hoping to make it to the Strip,” he re. “Then a guy went monkey on my back. He flipped me over and started screaming at me. I called the police and then I called Bob Nersesian [a Las Vegas attorney who specializes in representing advantage players against casinos].”

Because Treas had previously been warned against returning to the Wynn, he was arrested and told by Nersesian that he had no case against the casino. Chips and cash were confiscated, and he wound up in a cell with the human remnants of a drug sting. “I was sober, super extroverted and hanging out with a bunch of heroin dealers and addicts,” says Treas. “I figured I would encourage these guys and pray for them. At 5 or 6 a.m. I got released into downtown Vegas with a check instead of my chips and money. I had to figure out a way to get back to my room at the Venetian.”

Hours later, Treas had another run in, this one at Bellagio while trying to cash out $54,000 in chips that he could not for because he didn’t use his player’s card when he won them. Security interrogated him for a while, and the casino refused to accept his chips, but Bellagio eventually allowed Treas to leave—with his chips, which the team could use for playing. Nevertheless, the ordeal caused him to miss his flight home and his blackjack career ended on a pair of sour notes. “That was it,” he says. “I never went back to Las Vegas again.”

Treas says he was burned out, backed off across the country and looking for something more rewarding than blackjack. He left the team to form a test-preparation company called Torch Prep. To him, cracking the code of the standardized test was a lot like cracking the code of blackjack. Plus he has the potential to make more money, help people and not need to spend time in casinos where, despite his rationalizations, he was never 100 percent comfortable. “It’s not that blackjack is bad,” says Treas. “But it’s not good enough. It doesn’t bring more awesomeness to the world. I rendered it unworthy for myself and it’s not the life that I would want my son to live.”

In 2010—while the team was in the midst of a nasty downswing, resulting in part from fatigue, possible theft and a kind of malaise that sets in when it becomes increasingly difficult to play—Ben Crawford had similar sentiments. He decided to call it a day as well. He completely turned over the reigns of management to his Bible camp buddy Colin Jones. Crawford went on to cofound a company called Epipheo Studios, which got its start by using stick-figure animation to simplify difficult concepts for companies that include Google and Microsoft.

He doesn’t regret his years of playing blackjack and managing the team. But when I asked him to hit a local casino with me, just for the sake of the story, he refused. The thinking was that we would have to drive a fair distance and there was a chance that he’d get thrown out before he even began to play. Or, worse, he’d run bad and lose money in an effort to show off. What Crawford says he got out of blackjack “is an opportunity to be an entrepreneur. I know that I’ll never go back and work for another person.”

In the end, Jones was left to salvage a sinking ship. That the team had agreed to cooperate for a documentary indicates how lackluster things had become. He, too, was worn down by the enterprise. He believed that his head was no longer in the game and felt uncomfortable being responsible for investors’ money under those circumstances. The team was also mired in a two-year net losing streak—which, Jones acknowledges, had to do with issues other than bad luck. That didn’t

exactly help things either. In 2011 he finally informed investors that they’d be taking a loss and disbanding the team. He now runs a website and training service called blackjackapprenticeship.com.

He looks back on the experience with more fondness than Treas and Crawford and gives the impression that he wouldn’t mind getting back out there under the right circumstances. All and all, he says, it wasn’t a bad deal. Beyond the opportunity to achieve something that few people can, Jones says, “I made around $700,000 over the eight year period. I started with only $2,000 and it was pretty slow for the first couple of years. The point isn’t that we made so much money. It’s more that we won it from casinos.” He hesitates for a beat, then adds, “But the weird, bigger picture thing is that we think all money is God’s money anyway.”

Michael Kaplan is a Cigar Aficionado contributing editor.