The Survivors

The scene: a cigar dinner in New York City in the mid-1990s. A burly, goateed man wearing a blue suit walks up to two smokers, a simple, unvarnished box of cigars tucked under his left arm. He offers his right hand in a shake. "Doug Wood," he says with a small smile and a sleepy, friendly gaze. He launches into a casual, short speech about the merits of his cigar—one of dozens and dozens of unknown brands invading a booming market—and hands one to each of the men. It's a process he'll repeat over and over for years. Nearly a decade later, Wood is still selling cigars. His La Perla Habana and Black Pearl brands, while hardly mainstays in most stores, sell well enough to earn him a living. That's more than can be said for many of his cigar-boom contemporaries, now long gone, off to try new businesses after their brands faded into obscurity. Today's cigar industry goes beyond the giants Altadis and Swedish Match, the iconic Padrón and Fuente families, and hardy boutique cigarmakers such as C.A.O. and La Flor Dominicana. A number of companies survived the post-cigar-boom fallout through persistence, creativity and sacrifice. The following survivors have each crafted a niche in the cigar market.

LA PERLA HABANA

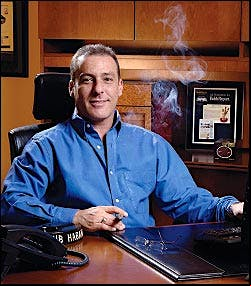

When Wood entered the cigar market in 1996 he couldn't rely on it as a sole income source and was forced to make ends meet as a driver for actors and producers in Hollywood. He also owned a stake in a Beverly Hills cigar bar. "It was difficult," he says, sitting behind a simple table at his modest booth at a recent trade show. His sister serves as spokesmodel and greets tobacconists, and a neighbor helps him take orders. His company, Burlwood Group Inc., has three full-time workers. "I can the days when I didn't have cable TV because they shut it off. I couldn't pay the bill. I'd like to say the company is rich. It's doing well. Now I have a beach house and things are good."

Wood survived in the shadow of the industry giants by treating small orders with respect. "Smaller retailers, that maybe couldn't get an with Fuente, found us, and stuck with us. Mom-and-pop tobacconists," he says. "A lot of cigar companies that got in during the boom wanted to cash in. They weren't willing to send out the two and three boxes a month to the little customers. There were a lot of cigar companies that didn't want to mess with that."

Like many smaller cigar companies, Wood doesn't make his own cigars. The Toraño family makes his Black Pearls and La Perla Habanas in Honduras and Nicaragua.

Wood still specializes in small orders, finding a receptive ear in cigar shop owners with crowded humidors. The little shipments aren't feasible for bigger companies. Some cigar shops, says Wood, "can't do 10 different sizes, they can't do a bunch of everything, but they can take three or four of our best cigars. We make cigars one at a time, and we sell cigars one box at a time."

ALEC BRADLEY

|

Alan Rubin its he has bad timing. He entered the cigar business in 1997, the year sales began to slow across the industry. "It couldn't have been worse," he says. "Most of the people who started when I did are gone."

Rubin, now 44, was an importer of bolts, nuts and screws made in China and Taiwan, and had success with a product built to meet hurricane codes. As business grew, he and his father sold the company for a comfortable sum that allowed Rubin's father to retire and gave Rubin the freedom to pursue a new field. "I just decided that whatever I did next was something I would enjoy, something I'd have a ion for. Something that wasn't a commodity."

A ionate smoker who has enjoyed cigars since his early 20s, Rubin incorporated Alec Bradley in 1996, naming the company after his two sons, and served a one-year consulting contract with the buyers of his company before selling his first smoke. He had no history in the business save for the fact that his father and grandfather once sold cigars and candy in New York City.

"Our original business plan was to provide cigars to golf courses. Our first product was called Bogie Stogies," he says. "Being a Florida boy, I didn't realize half the country doesn't play golf six months out of the year," he recalls with a laugh. "It was a bad business plan."

Rubin next tried selling Gourmet Dessert Cigars—flavored, handmade, Cuban-sandwich-style smokes—for around $2.50 each. The Florida-made cigars kept the company above water, but times were lean. Rubin didn't draw a salary, and the company was losing more money than he realized.

"On April 19, 1999, my partner left," he says. Rubin looked over the books and was shocked. "We were almost bankrupt. I went home that day and I said to my wife 'I don't know if I can pull us out of this mess.' "

Rubin decided to stick it out one more year, and try to make enough to at least get his company out of debt. That summer, he met Rafael Montero, who told Rubin that Hendrik Kelner, the maker of Davidoffs, could make him a cigar brand. Rubin asked Kelner to put his famous name on the smokes, and they created a brand named after one of Kelner's factories, Occidental Reserve by Henke Kelner. (It was later renamed simply Occidental Reserve.)

Famous name or not, breaking into the saturated 1999 cigar market wouldn't be easy. Bargain bins were bursting with unwanted smokes, and established brands, such as Macanudo, were no longer back-ordered in the millions. Rubin sent out 500 sample packs of Occidentals to retailers, making no mention of price. "We just asked them to smoke it," he says. Rubin then told them they could have the cigars in bundles for just over $1 each, and the cigars would have a suggested retail price of $2.50. Orders came in. It was a ridiculously low price for a long-filler cigar made by one of the big names in the business, but it was the only way for a desperate Rubin to get the brand accepted.

"I put it all on the line. We were coming off a flavored cigar with no other brands. This had to work," he says.

Occidental Reserve allowed Rubin to pay his bills and eventually get out of debt. Alec Bradley showed its first profit around the end of 2000. "Things are doing particularly well [now]," he said in September. "August of this year was our best month in our history. Our growth is in double digits."

Montero is still employed by Rubin, and Kelner makes four of his cigar brands, which include Pryme, Alec Bradley Trilogy and Alec Bradley Havana Sun Grown. The Toraños and Nestor Plasencia make some of his cigars in Honduras, as does Tabacos Puros de Nicaragua in Nicaragua.

Rubin plans on selling "a couple of million" cigars this year. "We're a profitable company, we still put a tremendous amount back in the business; we're growing the business. You have to have a long-term approach to this business. We feel [customers] always get more cigar than what they pay for."

CUBAN CRAFTERS

Kiki Berger began making cigars in Nicaragua in 1996. "When I first got here, it was the time the Sandinistas had just left," he said in Nicaragua in 2003. "The country was just starting to boom. I went from a little factory to building a bigger one."

Unlike many of his boom-time counterparts, Berger showed his devotion to his craft by investing in his business and setting roots in Nicaragua. (He even married a Nicaraguan woman.) He planted a field of tobacco directly next to his factory on the Pan American Highway in Estelí, Nicaragua, and built a curing barn.

"The only way you can have good quality tobacco is, number one, you have to grow it, and, number two, you have to cure it. I look at Padrón," he says, referring to his more famous neighbor, who often invites him over for coffee or drinks. "And I look at his success. You have to copy the best."

Berger once focused on making cigars for other companies, whichincluded boomtime brands such as Cupido, but now he's spending most of his efforts on his own products, specifically his Cuban Crafters brand.

Berger proudly shows off his property to visitors, highlighting outdoor seating areas he's having built to allow workers or guests some moments of relaxation. He's outfitted an office with two old barber's chairs, which he plops into, kicking out his feet, a plume of cigar smoke pouring from one of his dark puros.

GRAYCLIFF

Of all the brands to survive the cigar boom, one of the most unlikely has to be Graycliff. Scores of new brands were driven from the market when older, established brands were able to increase production, and consumers realized that the famous brands were often cheaper than the newcomers. But one of the most expensive cigar brands created during the boom is still on sale today.

Graycliff cigars are made in Nassau, the Bahamas, and they debuted in 1997 in the United States with eye-popping prices, up to $26 for one cigar. Few things are cheap in the Bahamas, and importing tobacco results in steep import taxes. Labor is also costly when compared with Central America.

Enrico Garzaroli created the brand after he came to Nassau by way of Como, Italy, in 1974, and bought the Graycliff mansion. The landmark was created in the 1720s, and Garzaroli turned the palatial retreat into a posh restaurant and hotel featuring exquisite dining and first-class service, building a wine cellar with a stunning array of bottles from around the world. "I tried to have wines the people had never heard about," he says. "The food is only a piece of the puzzle."

Garzaroli is a huge man with a personality to match, and a zest for the good life. He'd long loved cigars, and fashioned Graycliff into one of the world's more cigar-friendly places. Ashtrays seem to cover every flat surface. The restaurant did a large business selling Cuban cigars, and once had its own Casa del Habano. A dispute with the Cubans led Garzaroli to create his own cigar factory right behind his hotel. With the aid of Avelino Lara, who once ran Cuba's famed El Laguito factory, Garzaroli set up a small cigar factory featuring retired Cuban cigar rollers.

It wasn't easy to sell such a pricey smoke in 1998 and 1999. "What I was producing was more than I could sell," says Garzaroli. "People wanted to pay ten cents on the dollar."

He resisted discounting his smokes and called on an attitude honed from running a first-class restaurant: Be picky in the face of tough times. He also was able to subsidize the cigar segment of his business with his core business, and always had strong sales in the Bahamas, both in his restaurant and in the Atlantis Hotel.

"We had pretty good faith," he says. "A lot of cigars on the market were pure garbage. So I said, 'Soon these fellows are going to disappear.' "

Despite the high prices, Graycliffs are still selling in the U.S., and last year about 1.2 million cigars from the Bahamas were sent to the United States. Garzaroli, who is now 60, also sells in Italy, Switzerland, Russia and other international markets. "It's not that we have a million dollar buyer, but we have a lot of very good persons that put them in the hands of the right people," he says. "Now the cigar company is almost even with the restaurant sales."

OLIVA

Oliva Cigar Co. seems poised to step up into the ranks of the more established cigarmakers. The company has been making cigars for only 10 years, but the family (which is not related to Tampa's Olivas, who grow and broker tobacco leaf) has been growing tobacco for decades.

The Oliva Cigar Co. began modestly, with Gilberto Oliva Sr. making cigars inside one of the Honduran cigar factories owned by Nestor Plasencia. He debuted the Gilberto Oliva brand in 1995. It was made with a typical blend of the boom years: Dominican and Nicaraguan fillers, Dominican binder and Connecticut-seed wrapper grown in Ecuador. A year later, the family opened its first Nicaraguan factory, and shortened its brand name to Oliva.

The cigars didn't catch fire in the 1990s, and Oliva soon found itself making a little-known brand in the midst of an industry-wide cigar shakeout. With money scarce and the family unwilling to go into debt, the Olivas turned to Gilberto Sr.'s stocks of Nicaraguan tobacco.

"My father, as a grower, had a good amount of tobacco aging," says Jose Oliva, vice president of the company. "For one-and-a-half years, he carried us with his inventory of tobacco."

The Olivas were forced to make Nicaraguan puros, which improved the product. Impressed by the change, the family "never again" imported filler tobacco. It still imports some wrapper leaf, which is sometimes used as binder.

Oliva's puros—even its less expensive smokes—have done very well in Cigar Aficionado taste tests. The company's Flor de Oliva 10th Anniversary brand retails for less than $3. The Oliva O Classic Ole, which recently scored 92 points, sells for just under $6.

Jose Oliva, 32, shows a visitor around his headquarters, located in a quiet neighborhood in Miami Lakes, Florida. He lights an Oliva Master Blend and sits down in the smoking room, a luxe, spacious area with leather couches and a selection of his company's cigars. (Some of them are private label brands Oliva makes for retailers, giving them a special touch by printing colorful bands, posters and other promotional materials.)

The room is a comfortable oasis, and comes in very handy in Florida, but soon it will be dusty from construction. Oliva is expanding, here and in Nicaragua. The company needs more room in Miami Lakes to store cigars, and is adding 3,600 square feet, most of it dedicated to cigar storage. Oliva also hopes to finish construction of a second cigar factory in Nicaragua, this one in the tobacco town of Jalapa, which will be half the size of its factory in Estelí, which replaced a smaller factory in the same town.

Oliva says his company will make more than six million cigars in 2005.

"Even though we are a 10-year-old company, our heritage goes way back," he says. "We have a much longer history." His grandfather also grew tobacco, and now the company grows in Estelí, Condega, Jalapa and Sommoto, Nicaragua.

GURKHA

Kaizad Hansotia, a man everyone calls Kaiser, built his Gurkha brand by concentrating on what he knows best—packaging. "I have no pedigree in this business," he says with refreshing candor. On a trip to Goa, India, in the late 1980s, he discovered a cigar called Gurkha for the Nepalese warriors who famously fought for the British, brandishing thick knives shaped like boomerangs. Taken with the name, he bought the inventory and the struggling brand for a pittance: $143. "I didn't know anything about the company," he says. "I wanted to give cigars as corporate gifts."

When cigar sales began to rise, Hansotia struck a deal with Miami Cigar & Co. to bring Gurkhas to the U.S. It was 1995. "It just didn't do well, " he says. "There were so many brands out there."

Realizing he needed to do something different to garner attention, Hansotia decided to go his own route. He had cigars made for him, and packaged them with skills he picked up in his family's watch business. He realized a box could be a problem. "No one wanted a cigar in a box," he says. "They didn't have enough room." Undeterred, he came out with a line of flavored cigars in tubes with a standup countertop display that didn't take up valuable humidor space.

The small brand built an audience, and Hansotia is selling the cigars for quite high prices. One of Hansotia's latest creations, the Gurkha Titan, comes in a heavy, brushed-aluminum box with four hinged doors and black engravings. The cigars inside are made by the Toraños and cost $20 each. "We needed a cigar for a unique smoking experience," says Hansotia. The packaging is impossible to ignore.

Gurkhas feature some of the cigar world's best packaging. The elaborate bands are heavy on the gold and silver. At the center is a large image of a Gurkha warrior in a rare moment of calm, testing the edge of his oversized knife with a finger, a wry smile appearing from beneath his mustache.

DREW ESTATE

Drew Estate was created in 1995 by fraternity brothers Jonathan Sann (aka Jonathan Drew) and Marvin Samel. Their first cigar was made in New York City, at Manhattan's La Rosa Cigars. It was a truly modest start. The duo's first trade show was in Orlando, in the summer of 1997, and Sann and Samel packed cigars and the company's trade show booth in a van and drove from New York to Florida.

The company soon outgrew the chinchalle in Manhattan, and turned to Nick Perdomo in Estelí to make a band called La Vieja Habana. Perdomo, who was in a smaller factory at the time, let Sann use some of his space. As both grew, Sann later set up shop in his own factory, and later still moved into Perdomo's old digs when Perdomo moved on to larger quarters.

Unlike many newcomers, and even some established cigarmakers, Sann took the bold step of spending most of his time in Nicaragua, where he has lived for nine or more months a year since the late 1990s. "At first, the tobacco growers didn't trust me because the boom had just ended and they saw me as just another gringo out to make a quick buck. When they saw that I was living inside the factory and I was relentlessly working hard every day, I began to earn their respect."

Sann had begun to make cigars with various flavorings, including rose petals and coffee. At the 1999 trade show, Drew Estate created an eye-grabbing booth with a chain link fence, colorful art and racing motorcycles, where it debuted the first cigar it made for itself, called ACID. (The brand isn't named for the hallucinogenic drug, but for the studio of a designer friend named Scott Chester, who owns Arielle Chester Industrial Design in New York.) The cigars, flavored with herbs and botanicals and with jazzy names such as Nasty and Kong Cameroon, were a hit. ACID soon established Drew Estate as the leader in the flavored cigar category.

Not that the company likes the term. "We don't use the "F" word," says Sann, who prefers the term "infused." Sann looks quite unlike nearly every other cigarmaker. At a cigar convention in early 2005, he sat in a crowded conference room wearing shorts, sandals and a white T-shirt. A large tattoo was quite visible on his calf. He was smoking one of his cigars, listening to someone in a polo shirt speak about taxation and its effect on the cigar industry.

Despite his appearance, Sann is a respected industry force. "He's probably one of the most creative guys in the industry," says Jose Blanco, marketing manager for La Aurora cigars. "He was way ahead of his time. Along with C.A.O., I think he's the biggest marketing genius in the industry."

Sann now makes the Kahlua cigar for distribution by General Cigar, as well as the coffee-flavored Java for Rocky Patel and the tequila-flavored Sauza. He also makes more traditional blends, without flavorings or infusions, such as Natural and La Vieja Habana.

CUSANO

|

Mike Chiusano was a Boston financial executive who liked to celebrate his big deals with his brother at Two Guys Smoke Shop. In 1995, he took a trip to the Dominican Republic, where he was handed an unbanded local smoke. He liked it so much he ordered 100 more. Using sheets of letterhead from his investment company, he fashioned a simple band, then proudly handed one to David Garafalo, one of the owners of Two Guys. The gift turned into the start of a business, and soon Chiusano had an order for 10,000 smokes. He ed a Spanish-sounding version of his last name, Cusano Hermanos, and he was in the cigar business.

"It was like a mistake. It just happened," says the 44-year-old Chiusano, a small, athletic man with off-the-charts energy. "Slowly but surely the cigar business just sort of took over, so I wound up spending all my time doing cigars. We got really serious about it when the numbers started getting bigger."

Getting serious also meant improving the source of his cigars, which were made by three cigar companies at one point. Chiusano used his charms on Katherine Kelner, the daughter of Hendrik Kelner, to wrangle a meeting at the 1997 trade show. "I gave him a Cusano Hermanos Connecticut, asked him if he would smoke it and asked him if he could make it. And he smiled and said 'I can make it better.'" Kelner now makes all of Chiusano's non-flavored cigars.

Landing Kelner as a cigarmaker meant that Chiusano needn't spend half his time in the Dominican Republic doing quality control on the sundry cigars. "At that time you couldn't trust what factories put in boxes," he says. Working with Kelner gave him consistent quality, even if he ridiculed Chiusano's early orders. "Our first order was for 20,000 cigars," says Chiusano. Henke laughed. He said, 'I'm looking for customers that can do two million cigars, not 20,000, but I like the underdog,' " says Chiusano.

The underdog proved creative, and part of the success of Chiusano's cigar brand—which is now called Cusano—is untraditional thinking. Chiusano was probably the first to put bar codes over the cellophane on his cigars, improving retailer inventory. At a recent show, his busy booth had plastic shopping baskets with the Cusano logo for retailers ordering enough of his product. It evoked images of happy cigar smokers, loading a basketful of smokes rather than tiptoeing to a retail counter and trying not to drop fistfuls of singles.

After four years without profits, the cigar business began to succeed. The brothers Chiusano spent less and less time on investments, letting the business "whittle away." They did their last deal in 2000 or 2001.

"We like to be a small cigar company. Volume wise, we're getting up there. We're not an Ashton or anything, but we're getting to the point where it's becoming sizeable." He says he'll sell close to 5 million cigars in 2005.

The perceived demographic of the cigar market, Chiusano says, is "the male, age 35 to 55, makes $100,000 a year, college educated, owns his own home and smokes three cigars a week. We target the guy who smokes three cigars a day. 'Cause that's who we are."

After the lean years of the late 1990s and early 2000s, survivors like Chiusano are profiting from today's handmade cigar market, which grew more than 9 percent in 2004 and was poised for an equally strong 2005 as this issue went to press.

Some in the industry have even used the word "boom" to describe the market conditions. New cigars are entering the market at a pace not seen since the 1990s. Recent arrivals include Tabacalera Las Vegas Co., run by Gabriel Miranda, formerly with El Credito Cigars; Dona Flor, a new brand from Brazil made by Felix Menendez, which tested the waters with a $10-plus smoke at this summer's Retail Tobacco Dealers of America trade show; and Los Blancos Cigars, run by U.S. Army veteran David Blanco.

Some newcomers have even created some buzz. Ernesto Padilla, who once worked for Tabacalera Perdomo, has taken high scores with his Padilla 8&11 Miami Blend, which is rolled at El Rey de Los Habanos, a tiny factory owned by Pepin Garcia. The same factory is home to the Tatuaje brand, owned by the Grand Havana Room's Pete Johnson, a longtime cigar retailer who created a full-bodied blend of his own in 2003. Rocky Patel, who entered the cigar business in 1996 with a partner on the Indian Tabac brand, has found fame and high ratings making cigars in Honduras under his own name. (See the February 2005 story "Rocky II".)

The ultimate boom survivor has to be La Flor Dominicana. Cigarmaker Litto Gomez entered the cigar market in 1994 and, in the short span of 11 years, has completely transformed himself from a maker of simple, mild cigars to an acclaimed tobacco grower with a library of brands including some of the world's most creative and full-flavored smokes. Examples are his groundbreaking and strong-selling La Flor Dominicana Double Ligero Chisel.

Some of the brands that disappeared during the post-boom malaise have even tried to stage a comeback, such as Oliveros, Tamboril and Fittipaldi, a cigar named after the legendary race car driver.

Each of these newcomers is trying to achieve what the survivors already have: doing enough to get noticed by cigar smokers and set themselves apart from the rest of the pack. Each hopes to become the next Cusano, Drew Estate or perhaps even a La Flor.

Looking back at the boom, Chiusano is proud to be one of the companies that made it through the boom. "Two hundred brands started, and multiple people did IPOs. We kind of bootstrapped it, made what we liked and charged what we thought was reasonable," he says, simply summing up his business strategy. "We're really cigar consumers. We just happen to also make them."