Tyrants of the Desert

The medieval metropolis of Budapest, Hungary, sits astride the Danube River, a wonderfully preserved historic enclave that survived both World War II and Soviet rule to emerge as one of Eastern Europe's most sophisticated cities, a vibrant jewel box full of Old-World charm. But a very different, even more ancient world has been constructed just a half-hour outside the city.

Astra Studios is a blocky gray building that looks like a multistory big-box discount store—think Walmart without the charm—dropped in the middle of the Hungarian countryside. Hidden inside is a paradise, the royally appointed presidential palace of the fictional Middle Eastern country of Abuddin, the setting of "Tyrant," FX's provocative and controversial series about the temptations of power and balancing the needs of family and country.

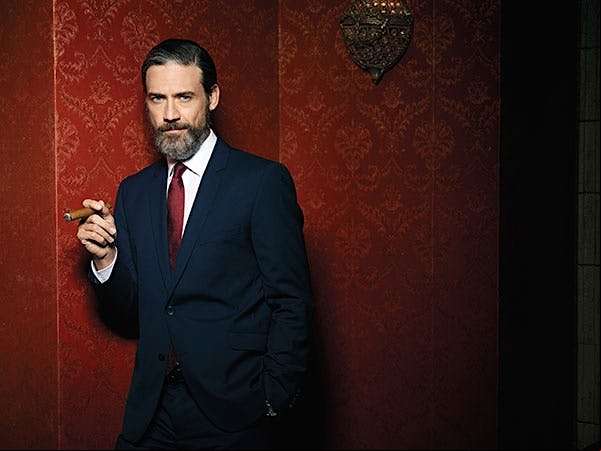

Adam Rayner looks extremely presidential as he sits in the splendor of the faux presidential dining room, waiting for his call to the set. A solid, wiry 6-foot-1, he's poured into a black suit that lends a certain power to his chiseled good looks. He's two episodes into filming the third season of "Tyrant," which debuts on July 6 at 10 p.m. on FX.

His character, Bassam Al-Fayeed, has had quite the journey in two seasons, returning to the Middle East and his aristocratic heritage after a self-imposed 20-year exile. The sudden death of his father, the longstanding and hard-nosed ruler of Abuddin, leads him to stay to help his older brother rule the country—only to end up abandoned for dead by his brother, who proves to be even more ruthless than his father. Season 2 ends in a cliff-hanger, with Rayner's character returning to the capital as a hero, his brother lying in his arms soaked in blood.

In a show that was conceived as an Arab version of The Godfather, think of this as the moment when Michael Corleone replaces his late father and accepts this as his destiny.

Rayner is really feeling the new role his character has been thrust into: newly appointed "interim" president of Abuddin. How long will he be able to stay presidential? That's another matter.

"Bassam keeps describing himself as ‘interim president,' " Rayner says. "But someone who can stick to that ‘interim' label—that's a rare beast. To have temporary power and then relinquish it? It doesn't happen very often. The lines become blurred between exercising power as a necessity to keep the country together and a personal need for power."

The journey of Rayner's character—emotionally, physically—has been at the center of "Tyrant" since its 2014 debut and helped make it the distinctive drama that it has become.

It's the only series on network or cable set entirely in the Middle East, mirroring headlines of the turmoil in a region beset by ancient tribal and religious enmity. While series such as "24" and "Homeland" have used exotic locales as backdrops for individual storylines, the stories themselves were firmly rooted in the USA. It took "Homeland" until its fifth season to focus all of its action outside the U.S.

Part of the reason is the cost of filming abroad: whether it's importing experienced crew, exchange rates, the availability of suitable equipment, soundstages and housing or simply the language barrier, it usually costs less to film in the U.S. or Canada than in Europe or the Middle East. Then there's also the question of viewer interest in people and stories set in other parts of the world.

"The idea of doing a show that's not set in America is unthinkable—most networks wouldn't consider it," says executive producer Howard Gordon, the award-winning creator of such hits as "24" and "Homeland." "Maybe—maybe—someone would entertain the idea of a show set in London. Doing a show in the Middle East, with predominantly Middle Eastern characters? Forget it. But FX stepped up."

"Traditionally, shows not based in the United States have not fared well on American television, except maybe ‘Masterpiece Theater,' " says Eric Schrier, president of original programming for FX Networks.

But "Tyrant" works, and thanks to lower costs of good facilities and crews in Hungary, it costs less to produce than "24" and "Homeland." And Gordon has a long-standing relationship with Fox, which aired "24" and whose parent News Corp. owns the FX cable network. "We wound up on FX because of [network president] John Landgraf's interest and ion to tell this story," says Gordon.

Despite FX sporting a tagline of "fearless" for its programming, Schrier its that the show represented a risk—if only of being accused of taking sides or playing favorites, because there are so many factions at play in the Middle East.

"We try to take big swings," Schrier says of the series, whose ratings were consistent enough to earn it a third season. "A show set in the Middle East? That's a big swing. The story was a really bold choice and that's why we're excited about it."

Taking a risk on ratings and revenue is one thing; filming in a war zone is something else. The entire production found itself in harm's way midway through the first season when war broke out in Israel, near where the production was filming.

"Let's say this show had its challenges, production-wise, that first season," Schrier says. "I mean, they were shooting rockets."

Recalls Gordon, "We picked up like a circus without permits, cast and crew, and relocated to Turkey and completed the season. Even then, there were issues of safety that made it hard for us to be bonded and insured."

For the second and third seasons, the entire production relocated to Budapest. For the third season, the palace interior has been expanded and elaborated upon in the soundstage confines. The palace rooms dazzle with their blend of gold, burnished wood and deep jewel tones. Historic-looking oil paintings share space with what appear to be actual antique pieces.

The personal chambers and official offices are spacious, laid out so that cameras can trail the presidential family , their servants and underlings as they move through their lives. A lavish dining room, classically appointed in dark earth tones, opens into the dramatically lit (and extremely contemporary) kitchen.

The studio is not far from the series' exterior set, a $4 million location that could double for the deserts of the Middle East.

A mile or so from the studio, down a barely paved road into a sand quarry, the production has built its own multipurpose city, with both interior and exterior sets. The city normally stands in for Ma'an, an oil-dominated border-desert town on the opposite side of the country from the palace. The city is home to various resistance forces, terrorists and other extremists that threaten the ruling power structure in Abuddin.

"We essentially built a backlot that houses a desert, a Bedouin village, a military base and a midsized city," Gordon says, "and that's impressive by any standards."

Enter on one side of that town and you're in a burned-out neighborhood with a tank sitting in the street. Turn a corner and there are cameras positioned outside a mosque. Step through an arched doorway to the outside of city walls and you face sand dunes that can double for the desert. Walk past one of the ubiquitous carved-wooden screens and you're in the square of the local university, which is a hotbed of protest against the regime.

The real drama, however, swirls around the palace, where Bassam Al-Fayeed stands squarely in the middle of all of it. Once an unassuming Arab-American doctor, now the new leader of a nation in political turmoil, the character is changing Adam Rayner's life, though he initially tried to avoid the role.

"When the script was first sent, I was quite busy so I was trying to get out of sending in my audition tape," he says. "My manager, to her credit, insisted."

The series pilot opened with Rayner as Barry Al-Fayeed, an Arab-born pediatrician living the American dream in Pasadena with his wife and teenage children. But Barry is actually Bassam Al-Fayeed, the son of the dictator of Abuddin. His backstory: After college, Bassam rejected his upbringing and left Abuddin for the United States, where he changed his name to Barry and went to medical school. Fully Westernized, with an American wife and two teenage children, he had not been back to his homeland in 20 years, when he agreed to return for the wedding of his nephew—the son of Barry's older brother, Jamal (Ashraf Barhom), the heir apparent to the presidency.

When their father dies unexpectedly, Jamal asks Barry to stay in Abuddin and help him run the country. Barry does, a decision that leads to his challenging journey: from working in his brother's brutish istration to trying to topple it in a U.S.-sanctioned coup, from escaping a death sentence for treason to becoming a mysterious leader of the insurgency and, by the end of the second season, forging an uneasy alliance with his brother to protect the country from religious extremists.

"The lesson, obviously, is that he really should have caught that flight home when he had the chance," Rayner jokes.

The second season ended with Jamal lying in a bloody mess on the palace floor, felled by a hail of bullets from an assassin within his own family in the show's final moment, his fate uncertain. The reins of power have ed to Bassam, its most vocal advocate for more democratic rule.

"The journey has been Barry's rediscovery of Bassam," says the 38-year-old British-accented actor, whose parentage—British father, American mother—means he carries dual citizenship. "He was very much Barry in that first season, but he rediscovered Bassam. In the second season, he was cast into the desert...He's returned to his birth country and to his original identity."

Rayner had a beard in Season 1, but he grew it in thicker during the show's second season. "When you're playing a president or a dictator, it's a time-honored cliché that a beard bestows authority on a man—or that's my hope, anyway," says Rayner. "People on the show have started calling me Abe Lincoln, which is an interesting comparison. I'm not quite sure if it's a compliment or not."

As Shakespeare wrote, "Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown." Jamal had his own take on that adage in the pilot, telling Bassam: "It's not easy being the son of a king."

That struggle for power—and the use of power once you have it—has been the focus of "Tyrant" since its inception. The show's creators and producers wanted to use the setting to explore those ideas, touching on the issues in the headlines while refraining from commenting on the policies and politics of any specific country.

"The Middle East is so complex that it's hard to get the right point of view without stirring up somebody," says Gwyneth Horder-Payton, the series' co-executive producer, who has also directed multiple episodes. "You can't please everybody, as we've found out. Because what's happening in the world now is so complex and dangerous, there will always be an opinion of which portrayal is the correct one.

"We have five cultural advisers in Los Angeles and one on the set here in Budapest. And they're often in conflict with each other. So we're all learning and trying to understand. We run into challenges all the time that expose our own ignorance."

She pointed to a moment in an early episode: Barry enters a mosque during prayers, walks into the center of the congregation and speaks to someone who is in the midst of worship. Horder-Payton found herself in the middle of momentary controversy.

"We built the set and hired extras of Arab descent. When Barry walked into the middle of the service, they were upset because they said this would never happen in a mosque—it would never be allowed," she recalls. "Plus here I am, a woman, in the mosque. Also not allowed. And I'm wearing shoes, because I'm going back and forth outside, where Video Village [where cameramen and directors watch the scene as it is filmed] is. Also not allowed. And they were serious, even though it was a set we'd built and not a real mosque. These kinds of things are a daily occurrence."

The fictional nature of Abuddin doesn't mask the way art is mirroring real life. The echoes of Syrian turmoil under Bashar al-Assad get stronger in the season for Bassam Al-Fayeed—and things don't seem to bode well for Bassam.

Gordon says, "As we were developing the series, it was interesting to us to consider the morning after the Syrian Civil War started and to imagine Assad and his wife, looking at each other and saying, ‘How did we get here from our nice home in Hyde Park?' He was an ophthalmologist in London. But it's also interesting to think about this: How does an aspirational leader become a person everyone thinks of as a monster, except through the exercise of power?"

"The parallels to Assad are obvious," says Rayner. "The old-style dictator father, the son who's been trained in the West. Still, it's important to say that this isn't a show about one country. That would prevent us from dealing with issues that are more common region-wide."

In "Tyrant," Jamal reflects the titular approach to governance. Bassam, a physician, has tried to present humane, humanitarian alternatives to his brother. But, Rayner hints, wanting to do the right thing and being able to actually do it can get tricky when you're the one in charge.

"The show was pitched to me as: A guy who's been running from his destiny comes back to face that destiny, by ruling the country he left behind," Rayner says. "I like to see Barry tested, and he will be. There are some heavy things happening that will shake him to his core and make him question his principles.

"Guys come into these situations with huge ideals. A tenuous security situation can force them to move away from those ideals because the country is not stable enough for fully free elections. The difficulty of having democracy without stability is a bit of a chicken-and-egg thing, isn't it? With Bassam, his theoretically more-progressive views turn out not to stand the tests thrown at him.

"You see a darkness descend on someone in a position of power, when they realize their enemies aren't playing by the rules. And they come to the conclusion that it's us or them."

This is Rayner's biggest role yet in a career that has taken him from the stage and TV screen in Great Britain to the starring role in an American cable-network drama. Not bad for a guy who says he started acting "for laughs."

"I was at university, at a moment in my life when I thought I wanted to have a go at something I enjoyed, before I came to my senses and had to get a real job," explains Rayner, who balances the call of family with the duty of work by living with his wife Lucy and toddler son Jack in an apartment in Budapest near the Danube while the show is in production.

He plunged into acting after college, earning a series of small roles in television and theater in London. "I had some great jobs early on, but you have to string them together to actually make a living. There tended to be big gaps at first but, by my late 20s, I relatively regularly got TV work in the U.K. I thought, well, I can pay the rent—and there are still 10 rungs up the ladder."

Rayner marvels at his own introduction to Hollywood. "I was just another actor getting off a plane in L.A. on January 6, 2010—and I was a regular on a TV show three weeks later. It's the only town in the world where that could happen."

The TV show was the three-season long TNT series, "Hawthorne," where he played a doctor opposite Jada Pinkett Smith. Al-Fayeed is the third doctor Rayner has played in his last four roles. "As I like to say, I'm not a doctor but I play one on TV," he jokes. "I can use that line in any emergency."

Acting brought Rayner to cigars. He had a small role in a production of Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing in London that was set in prerevolutionary Cuba. "The production bought us the cheapest cigars; they literally were falling apart in our hands while we were smoking them onstage," Rayner says. "They were revolting." Salvation came from a fellow actor named Joe Nelson, who brought in Cuban cigars. "He decided that as long as we were going to be smoking, we might as well enjoy ourselves....That may have been the most heavy cigar-smoking period of my life. Every night, I came in looking forward to that scene. There would be 600 people in the audience and these three guys in half-light, smoking cigars and listening to music."

Rayner tends to indulge in fine tobacco during evenings out in London with old friends. "We're spread all over the world, but we get together when we can. We'll put on suits and go to a nice restaurant and drink reasonably powerful spirits—and then the cigars will come out. My father and I will occasionally have a cigar together."

Rayner's tastes tend toward the traditional in Cubans: "I normally go straight to the Montecristos, the Romeo y Julietas," he says.

During one of the rare scenes of brotherly affection between Jamal and Barry in the first season of "Tyrant," the cigars came out. The cigars smoked in "Tyrant" inevitably carry a certain symbolism, given the context: "They're considered quite a Western symbol, associated with power and wealth, smoked by the Tony Sopranos of the world," says Rayner.

Casting Rayner as the Arab-born Barry/Bassam came "after a long process," Gordon says. "He needed to be someone who could be a TV star, who could hold a series. Adam hadn't done much but he had a strength—and women respond to him palpably on-screen, which is a good thing."

"Adam is an English gentleman and very charming. I have a lot of vulnerable scenes with him and he makes me feel very safe," says Moran Atias, the dark-eyed former model who plays Jamal's politically astute wife Leila—and Bassam's love interest from long ago. "Most of my scenes with him are emotionally intense, very full in that sense. I keep that emotion compressed and either let it out just before or immediately after a take. It feels good to find him there at the end of a scene like that, to hold on and tell me the work is good. It makes me feel safe. I trust him."

Atias takes an immersive approach to acting. When tasked with playing a gypsy, she moved to Rome and lived like a gypsy for three months prior to the shoot. But, as an Israeli Jew cast as the wife of an Arab dictator, she was even more determined to get inside the role. She read books by and about powerful women—everyone from Queen Noor to Hillary Clinton—to understand both the surface and the substance of that life. She also studied the Koran ("That's the first textbook of the culture,") and took horseback-riding lessons. "It's a process that never ends," she says of researching her role.

"These living characters feed my choices in creating the character of Leila," she says. "It takes time to build layers. Once you have those layers, you can create contradictions in the character that make her more interesting than a one-dimensional portrayal."

As a peace activist in Israel, Atias also understands the importance of a show like "Tyrant" in opening channels of communication. "To me, this matters. It's an incredible opportunity to work with Arab artists. Through art, walls fall."

Atias brings a laser-like intensity to the role, her stunning smile giving way to an expression reflecting the seriousness of the idea at the center of the only drama on television that confronts the day-to-day existential question of living in the Middle East.

"How do you trust your enemy, someone you know wants you dead?" she asks. "These questions—they're really embedded in this season."

Barhom, who plays Jamal, broke into American film in 2007's The Kingdom, and personifies the complexity the show seeks to explore. Israeli-born, he went to Haifa University. A Christian Arab, he is barred from entering Saudi Arabia because he has an Israeli port.

But, as he once told Denver's Westword weekly, "Art is the place where people can meet as individuals and come together. When we attach ourselves to national identities, then we enter into a cycle of conflict. I didn't choose where I was born or who to be or what people would call me. I'm a hybrid, from a cultural perspective, but I don't think in these . I'm more simple than that. I'm a mammal who will live 70 years, more or less, who believes in God and likes his life."

Unlike Atias and Barhom, Rayner is from the West, not the Middle East. "Obviously it's a challenge for someone with no experience of the Middle East to play someone from there," says Gordon. "Adam has been up to it."

"My main research was reading about the region," explains Rayner. "I'm not playing someone who was fully culturally an Arab man—to him, this world had become alien. Still, I was learning about Bedouin and Arab culture, the history and politics, as well as the current political climate, trying to gain an understanding and knowledge that Bassam would have grown up with."

Rayner has a general understanding of where the Season 3 plot will take his character as he assumes the presidency of Abuddin. But he's reluctant to look too far ahead.

"Part of the fun is to be surprised as you go along," he says. "Others are keener to know the long arc than I am. I think there's a benefit in not knowing. The character doesn't know. So I don't want to fill my head with where we're going next. It doesn't serve any purpose to know the endgame when you're at Episode 1, trying to discover your character."

At this point, that character has had power thrust upon him by events beyond his control. How will Bassam react to even a temporary dose of its seductive effects? "What's the saying?" asks Rayner with a smile. "Power corrupts?"

If outside forces eventually push Bassam Al-Fayeed to exercise dictatorial power to maintain order, can he somehow keep his ideals intact? As Rayner points out, history suggests otherwise.

"How do you rule over a democracy when you've got a gun to your head?" he says. "One easy way to solve the problem is to get a gun to the other guy's head. It solves the problem—but it's not democracy...How do you create security for the country without compromising those democratic principles? Democracy requires a lot of preparation, with elections after you've educated the people. But how long will that take? And who's in charge in the meantime? It's not as simple as, well, we got rid of Hussein or Qaddafi and now we'll have democracy.

"Because to build the democratic process, first you have to delay the democratic process—and that's an authoritarian government," he says.

Rayner's words echo through the vast splendor of the fictional opulence of his character's palace as he ponders these thoughts, his words hanging heavy in the air. "We want it to be better, but how long are we willing to wait? Those are all tough questions—aren't they?"

Contributing editor Marshall Fine is critic-in-residence at The Picture House Regional Film Center in Pelham, New York.